Bourbon Vs. Bourbon: Did Whiskey Really Taste Better in the 1800s?

If you ship whiskey on a river, does it taste better? We wanted to know, so we ran an experiment.

Jacqueline Detwiler STUART TYSON

STUART TYSONThere’s an old story in the whiskey world: Before trucks and bottling lines, all American whiskey was aged and shipped in barrels, soaking up flavor as it sloshed down the Mississippi River. Eventually, people took a particular liking to the barrels marked “Bourbon County, Kentucky.” They started clamoring for “bourbon.” And that’s how that whole thing got started.

Trey Zoeller, the cofounder of Jefferson’s Bourbon and a man with an experimental streak as wide as a barn door, wondered if something had gotten lost in the decades of progress that followed. “In my mind, bourbon proliferated in Kentucky because of the route to market and not, as most people claim, the limestone water,” says Zoeller. To test that theory, two years ago he sent two barrels of Jefferson’s signature spirits along a traditional bourbon shipping route, down the Ohio River to the port of New Orleans and then into the Atlantic and up to New York City. The day he arrived in Manhattan to taste it, he brought the first sample, along with a control batch from Louisville, to Popular Mechanics. The whiskey that took the trip, which Zoeller calls Jefferson’s Journey, was mature beyond its age, richer, with new flavors of tobacco, vanilla, caramel, and honey. It was some of the best bourbon any of us had ever drunk.

SINELAB

To see if something had changed, on a molecular level, in the Journey to make it taste better, we partnered with Good Housekeeping Institute chemical engineer Birnur Aral and scientists at Jordi Labs in Mansfield, Massachusetts.

The Results

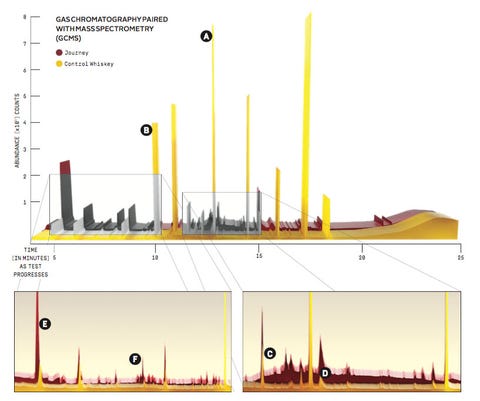

Jordi Labs analyzed two samples—Jefferson’s Journey and an age-matched control from the same batch that remained in Louisville the whole time—and the researchers performed two tests: gas chromatography paired with mass spectrometry (GCMS) and liquid chromatography paired with mass spectrometry (LCMS). “The GCMS is really good at detecting things that you might smell, while LCMS sorts out molecules that you might taste, although there is definitely some overlap,” says James Woods, one of the scientists who worked on the study. In both tests, specific molecules tend to pop out at specific times. Far more differences were shown in the GCMS, so we chose to focus on that, below. The X axis shows the time as the test progresses. The Y axis is basically an abundance counter: the higher the peak, the more of a particular molecule there is in the sample.

SINELAB

First, look at the huge spikes in the age-matched sample that sat in Louisville. “There are a lot of these large aliphatic esters, such as (A) decanoic acid, ethyl ester, which has a waxy, fruity, sweet-apple smell,” says Leland Martin, an author of the report. Another spike is (B) phenylethyl alcohol, a common floral note in whiskey. The higher presence of these elements in the control could explain why it tastes younger than Jefferson’s Journey. While these tests can’t show exactly how the components of the bourbon broke down during its travels, Journey contains a more diverse range of aromatic compounds, any of which are potentially degradants of components in the control whiskey. The chemicals that appear in greater quantities in Journey include (C) whiskey lactone, which gives whiskey a creamy, coconut-wood flavor and is often used as a flavoring agent in things that are supposed to taste like whiskey, and (D) isovanillin, which smells like vanilla.

Jefferson’s Journey also contains a higher amount of (E) furfural, a chemical with a woody, nutty, burnt-caramel flavor that comes from freshly charred oak barrels and can be used to authenticate whiskeys that have not been adulterated with caramel flavoring. It has a higher amount of (F) 5-methyl furfural, which tastes like maple and grain and is formed during both the Maillard reaction (the browning of meat and baked goods) and the caramelization of sugar.

No comments:

Post a Comment