Critics Roast the Army’s Battlefield Nuclear Reactor

The Army wants a reactor to power remote military bases, but critics claim it's unlikely any design would be safe enough.

By Kyle Mizokami BUREAU OF THE ATOMIC SCIENTISTS

BUREAU OF THE ATOMIC SCIENTISTSYou can see the logic behind the idea. The U.S. army envisions a kind of portable nuclear reactor that could move with units and provide all the power needs for a remote military base, eliminating the need to transport lots of fuel and maintain long supply lines to keep a base fueled up. But a prominent nuclear organization just weighed in, arguing that such a plan is a colossal mistake.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—the people known for their "two minutes to midnight" Doomsday Clock—argues that while such a reactor probably is feasible from a technical standpoint, it would never be safe enough to deploy on the battlefield. The risk of meltdown and radiation release would be too great ever to justify deploying the reactor into the field, the scientists say.

Nuclear on the Go

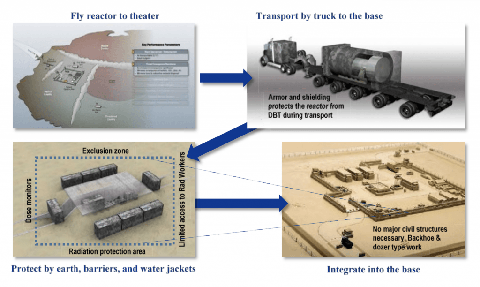

The Army announced Project Dilithium, its effort to develop a portable nuclear reactor, in January 2019. According to its plan, the reactor “should be less than 40 tons total weight; small enough to be transported by truck, ship, and aircraft; able to run for at least three years without refueling; and capable of semi-autonomous operation.”

Why the sudden interest in nuclear power? The Army’s return to big power warfare against the likes of Russia or China is driving a new emphasis on powerful radars, communications, and direct energy weapons, and that's probably what's behind this request, since all those systems are power-hungry. Portable nuclear reactors are also useful for conflicts such as Iraq or Afghanistan, where convoys laden with diesel fuel are at risk of ambush.

The Army wants a reactor capable of making 1 to 10 megawatts of electricity, and is clear that the reactor needs to be safe, incapable of melting down and contaminating nearby troops with harmful radioactivity. The Army emphasizes safety and trouble-free operation, but also acknowledges that such a reactor is “not expected to survive a direct kinetic attack.”

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists says a hassle-free, low-maintenance reactor is unlikely at this point of technological development. In addition, war bring a variety of inescapable problems; a reactor on a battlefield could be buried by debris or damaged to the point that it can no longer cool itself. If the reactor is unable to prevent its temperature from spiking, its military outpost could have a big problem on its hands in the form of a meltdown.

The Worst Case

Given the unpredictability of the battlefield, it's impossible to say for certain that a reactor could be protected from such catastrophic damage. And if a reactor does suffer a containment failure, the Bulletin says, it is hard to see how dangerous radioactive material isn’t unleashed into the nearby environment:

“An operating nuclear reactor is essentially a can filled with concentrated radioactive material, including some highly volatile radionuclides, under conditions of high pressure and/or temperature. Even a reactor as small as 1 megawatt-electric would contain a large quantity of highly radioactive, long-lived isotopes such as cesium-137—a potential dirty bomb far bigger than the medical radiation sources that have caused much concern among security experts.”

Another problem with Project Dilithium? The reactor could run on highly enriched uranium (HEU), which can also serve as fuel for nuclear weapons. The U.S. and other major powers have acted to reduce the amount of HEU in the world. But if other countries follow the U.S. Army’s lead it could result in more of the material worldwide, and the possibility that some of it could fall into the wrong hands.

No comments:

Post a Comment